A Harvest of Hope: A Colorado Farmer Sows the Seeds for the First National Registry of Bone Marrow Donors

Author Connie Boyd is a medical writer who lives in Denver, Colorado. Original article from BRIDGES (Winter 1987-1988)—St. Paul Red Cross Magazine of Community Affairs.

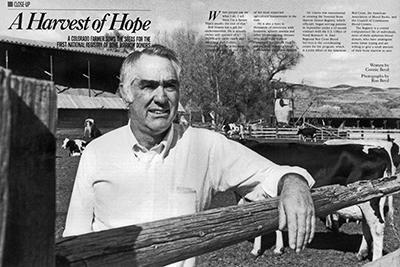

“When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m a farmer. That’s usually the end of that.”

Bob Graves has a gift for understatement. He is actually owner and operator of a 20,000-acre cattle ranch and dairy near Fort Collins, Colorado. He has a doctorate in veterinary medicine and is one of the most respected agricultural businessmen in the state.

He is also a hero to thousands of Americans with leukemia, aplastic anemia and other life-threatening diseases who need bone marrow transplants but cannot find donors with matching tissue types within their own families.

Dr. Graves was instrumental in creating the National Bone Marrow Donor Registry, which officially began serving patients in September under a 42-month contract with the U.S. Office of Naval Research, St. Paul Regional Red Cross Blood Services is the coordinating center for the program, which is a joint effort of the American Red Cross, the American Association of Blood Banks, and the Council of Community Blood Centers.

The Registry is a central computerized file of individuals, most of them apheresis blood donors, who have undergone some tissue typing and are willing to give a small amount of their bone marrow to save the lives of others. About 15,000 people have already agreed to participate, and it is hoped that at least another 40,000 will be recruited eventually. “Anyone who knows the facts will be willing to become a donor,” Dr. Graves said.

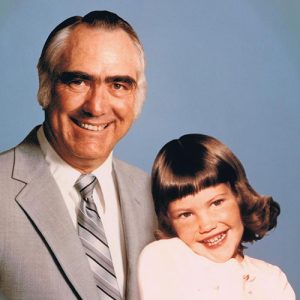

His conviction comes from personal experience, Eight years ago, his ten-year-old daughter, Laura, was dying of acute lymphocytic leukemia. The doctors at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, where she was being treated, said that a bone marrow transplant from a genetically matched donor was her only chance for survival.

But testing revealed that no member of her family had the same human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers on their white blood cells as Laura did. These substances are a part of the immune system involved in recognizing and attacking foreign tissue. If the are not compatibly matched in bone marrow donor and recipient, the transplant may end up destroying the body in an agonizing and deadly reaction known as graft-versus-host disease.

Before 1979, the news that no relative qualified as an HLA match was a death sentence heard by 60 percent of patients in need of the transplants. Up until that time, no patient had ever received bone marrow from an unrelated donor. Donnell Thomas, M.D., and John Hansen, M.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Center asked Dr. Graves and his wife, to consider allowing their daughter to be the first.

“We came back home and wrestled with it for two weeks,” Dr. Graves said. “The risks were enormous. Nobody knew what kind of monster we might create, what kind of horrible death we might be subjecting Laura to. But finally we decided to go ahead. We felt that if there was any possibility that she would live, we had to give her that chance.”

One factor influencing their decision was that a tissue match had been found, a lab technician at the Fred Hutchinson Center whose HLA type was on file because she was a regular donor of blood platelets. Dr. Hansen, director of the cancer center’s tissue-typing laboratory, said it was almost a miracle to find a qualified donor at the Fred Hutchinson Center, since the odds of finding two unrelated people with the same HLA characteristics are generally about one in 20,000.

To destroy all traces of her leukemia, Laura was given massive doses of radiation and chemotherapy. Bone marrow from the donor was transfused into her bloodstream to replace the diseased tissue. And the waiting began.

For 90 days, the little girl lived in isolation in an eight-by-ten-foot cubicle, a germ-free bubble, with her parents and the doctors watching anxiously to see if the transplant would take. As Laura gradually grew healthier and showed no adverse effects, it became clear that the gamble had paid off, not only for her but for other patients as well. Medical history had been made.

Over the next several months, Bob and Sherry Graves received a flood of calls from parents across the nation desperately seeking unrelated bone marrow donors for their children. Dr. Graves would spend hours on the phone trying to find a suitable HLA match. More often that not when he succeeded, the patient was already dead.

“It became obvious that some kind of central registry had to be established,” he said.

Dr. Graves set out to make it happen with the collaboration of Dr. Hansen and of Jeffrey McCullough, M.D., the director of the St. Paul Red Cross Blood Services, who developed a proposal for the program.

Armed with political savvy learned “in back rooms filled with cigar smoke” during his childhood in Colorado, Dr. Graves travelled from one end of the country to the other in a tireless campaign to gain start-up government funding for the National Bone Marrow Donor Registry.

“Along the way, we picked up some valuable allies,” he says. “The staunchest was Senator Paul Laxalt of Nevada. Every time we came to a major crisis, I gave Paul the opportunity to get out. He never waivered.”

It was Senator Laxalt who inserted a paragraph in a defense subcommittee report stating that the U.S. Navy would establish a national registry of potential bone marrow donors. This paved the way for the contract awarded by the Office of Naval Research in 1985.

An independent board of directors was named to administer the contract, with Dr. Graves as chairman. Several prominent and highly committed people have been recruited to its ranks. One is Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, Jr., whose son, Lieutenant Elmo Zumwalt III, underwent a bone marrow transplant at the Fred Hutchinson Center early in 1986. Another is Armand Hammer M.D., the well-known industrialist.

Laura Graves died from a relapse of her leukemia in 1981. The extra year-and-a-half of life she was given by her transplant was precious to her and her family. “She lived life to the fullest right up to the last day,” her father says. “If we had to do it all over again, we’d do it in a minute.”

Dr. Graves and Admiral Zumwalt recently testified before Congress to request a $1.4 million appropriation to carry out the Navy contract over the next fiscal year. They were given $2.1 million instead, along with several compliments on the importance and value of the project. After an eight-year battle to get the Registry started, its future appears assured.

“Creating this thing has been like planting a crop,” Dr. Graves said. “After all the work to get it going, now it’s time for the harvest.”